History

Sázava Monastery has a thousand-year memory from 11 century.

It is also place of the Kingdom Come: Deliverance I. videoplay.

Tours are possible in Czech group with a guide or video application or with text in English, German, Polish, Russian without a guide separately - exteriers and interiers.

An ancient monastery towering on a rocky cliff over one of many meanders of the romantic Sázava River is referred to in connection with the Bohemian national saint, St. Procopius.

In the early times, the monastery was famous as a center of Slavic liturgy and education. So far, it’s been the place of pilgrimage to St. Procopius, and the authentic witness of ten centuries of the Czech history, with numerous buildings from various historical eras and art styles.

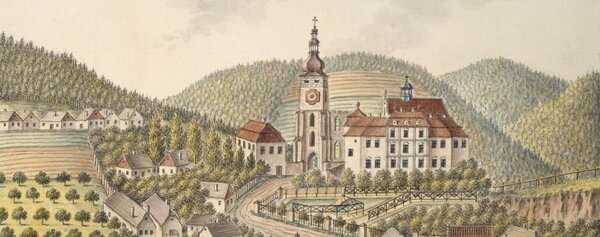

J. A. Venuto, Sázava, 1822 (by picture from 1786).

The beginning and the Romanesque Slavic era

The third oldest male monastery in Bohemia is located in the area where a hermit called Procopius settled down in a cave in the early 11th century. Over time, he built a community of hermits that turned into Benedictine monastery in 1032, thanks to the Přemyslid dukes Oldřich and his son Bretislaus. The monastery was special during the entire 11th century for its Slavic liturgy. With this, it followed up on the legacy of the missionaries of the Great Moravia, St. Cyril and St. Methodius (9th century). The Slavic Benedictines created numerous important Slavic written relics in Sázava. The monastery also became famous as a place where the poor and the ill found help and assistance. Abbot Procopius died on March 25, 1053, with the reputation of a saint. He was buried in the wooden temple that he built with his companions; soon after that, the community chose his nephew Vitus for the new abbot. However, hard times were coming for the Slavic monastery.

In 1055, during the reign of Prince Spytihněv II, Procopius’s disciples were cast out of Sázava. They left for Hungary, and spent six years in the Basilian Slavic monastery in Visegrád. It was probably here where they befriended the monks from Kiev, which paid well after their return to Bohemia in 1061, upon the invitation by the prince, and the future first Bohemian king, Vratislaus I. A period of fruitful contacts and cultural exchange with the monks of Pechersk Lavra followed. Sázava became a crossroad on the cultural borderline between the Western and Eastern Christianity. In this era, the first stone church was built in the monastery area, consecrated to the Holy Cross in 1070. It was used by the laymen working for the monastery. The archaeological foundations of this church can still be seen in the northern garden of the monastery area; the model building for the church was the Anastasia temple in Jerusalem.

After abbot Vitus’s death, the brethren elected Procopius’s son Imram, and then new abbot Božetěch. This excellent artist, painter and sculptor, started building another stone building in the monastery area in the late 11th century. The simple wooden church, used by the monks for everyday prayers and also home of Procopius’s grave, was no more suitable for its purpose, and Božetěch turned it into a Romanesque basilica.

In 1095, a part of the basilica – the chancel – was consecrated by Cosma, Prague bishop. During the ceremony, the relics of the first martyrs of Kievan Rus, the brothers St. Boris and St. Gleb, were inserted to one of the altars. Shortly after that, another heavy blow hit the Slavic monks. In December 1096, during the reign of Prince Bretislaus II, they were cast out for the second time. The Slavic prayers in Sázava were no more, and written Slavic documents were destroyed.

The Romanesque Latin era

In the beginning of 1097, Latin Benedictines from the Břevnov Monastery came to Sázava, led by abbot Dědhard (1097–1133). Under his leadership, the monastic life, reconstructions, creative activities and popular worshipping of Procopius continued, though Procopius still wasn’t an official saint. Under the following abbots Silvester (1134–1161) and Reginard of Metz (1162–?), a spectacular basilica was finished, and so did all other Romanesque buildings in the monastery area. Also the history of the monastery was written in Latin, including St. Procopius’s biography. This chronicle, recording events until 1177, is now known as the Chronicle of the Monk of Sázava. During the reign of the first hereditary king of Bohemia, Ottokar I, an important event occurred in the Romanesque temple. On July 4, 1204, Procopius was officially canonized in Sázava, in the presence of abbot Blažej, king Ottokar I and cardinal Quido.

The Gothic era

Under the last Přemyslid kings in the second half of the 13th century, other reconstruction started. The Romanesque basilica gradually turned into a Gothic one. During the reign of Charles IV, Sázava became home of the ironworks of Mathias of Arras, the original master builder of St. Vitus’s Cathedral. The basilica no longer had three naves of the different height; instead, a monumental three-nave structure was built. Also other monastery buildings were rebuilt in the Gothic style. So far, the visitors of the former convent can see, for example, the capitular hall with wonderful rib vaults, an interesting pillar with the sculptures of basilisks, and unique wall paintings.

Also attractive is the Madonna of Sázava, unique by its content and artistic design. Unlike typical paintings of this kind, this doesn’t depict Our Lady with baby Jesus in her arms; instead, she holds his hand, he walks beside her and carries a basket with colorful marbles. The architecture of the hall dates to around 1340, and in terms of style, it’s very similar to the works of the Augustinians from Roudnice. The Marian paintings on the walls were made between 1360 and 1380. However, the Gothic temple has not been finished yet.

In 1421, Prague Hussite troops invaded Sázava, all monks and builders were cast out, and the building was interrupted. Only the chancel has preserved until these days, covered by the Baroque buildings (the contemporary church), and the torso of the southern nave, with the tower made of red sandstone from Nučice. For more than two centuries following the Hussite wars, the monastery was owned by various irresponsible secular owners (the houses of Kunstat, Slavata of Chlum, Švihov, or Wallenstein) and gradually decayed. Also the reverence of St. Procopius declined – it had its peak during the Gothic era, in the times of Charles IV, when St. Procopius was the unchallenged patron of the land. These were the times of Vita sancti Procopii maior, and the Legend of St. Procopius. St. Procopius was also depicted in Charles’s cathedral in Prague and at other places in the Kingdom of Bohemia.

The early Baroque

In the mid-17th century, the monastery was once again in its prime, up to par with the glory days of the Romanesque and Gothic era. The abbot of Břevnov and Broumov monasteries, Seifert, bought the whole monastery area from the Wallensteins back for the Benedictines in 1663, together with a large part of the former domain. The Baroque recovery is connected with abbots Ildefons Nigrin (1664–1679), Benedict Grasser (1681–1696) and architect Vít Václav Kaňka. The latter’s autograph, written by red chalk on the wall, can still be seen in the church crypt. In addition to new development, the reverence of St. Procopius was also restored. Lots of pilgrims started pouring into the monastery once more. Since the early 18th century, various pilgrimage spots were made in the landscape around the monastery, referring to stories of St. Procopius’s life. At those times, the Bollandist legend was created, or the “Glory of St. Procopius” by Fridrich Bridelius. Around the same time, the reverence of St. Procopius gave also birth to the painting “Love Picture of St. Procopius”, placed in the church; the face was said to show miraculous effects. These effects were even confirmed in 1711 by the investigating committee of the Prague consistory.

High Baroque and Rococo era, with the end of the monastic life approaching

The fire in 1746 severely damaged the monastery and its decorations, yet it didn’t affect its heyday. The abbot Anastasius Slančovský (1744–1763), together with the architect Kilian Ignatius Dientzenhofer and important artists of the day, such as the woodcarver Richard Práchner or painter Jan Karel Kovář, organized the late Baroque restoration, with touches of Rococo. So far, you can see the Rococo altar in the pilgrimage temple of St. Procopius, with the painting “The Assumption of Our Lady” by Jan Petr Molitor, stucco decorations and the fresco “The Meeting of Hermit Procopius with Prince Oldřich” on the ceiling. Other works include “Abbot Procopius Giving Alms” in the convent refectory, or the frescos depicting scenes of St. Procopius’s life and the history of the monastery, recently discovered under many layers of paint in the cloister, and currently gradually restored. There were also various literary works: the Sázava monk and writer Hugo Fabricius wrote a new biography of St. Procopius and his miracles, called “The Blessed Legacy of the Big Miracle Worker of the World, St. Procopius”. However, at the top of its Baroque prime, the monastery was closed down by the decree of Emperor Joseph II in 1785.

The chateau era

The first secular owner was Wilhelm Tiegel of Lindenkrone in 1809. He began to use the area as chateau, only he had to acknowledge that there was a functional church and parish management in his chateau area. After the monastery had been closed down, the original monastery church became a parish temple. In 1869, the Tiegel family sold the domain to Johann Friedrich Neuberg. He started the reconstruction of the main building in the classicist neo-renaissance style to adapt it for more comfortable chateau housing, and to give it the modern design of the day. That was the time when the baroque frescos in the cloister were painted over, and the cloister itself was rebuilt by adding brick partitions. Also new was the neo-renaissance square tower above the convent building, the main purpose of which was to change the visual design of the monastery. Only seven years later, the Neuberg family sold the domain, including the chateau, to the landowner Friedrich Schwarz. In 1932, one of his heirs sold a part of the area to Benedictine monks from the Emmaus monastery in Prague, who wanted to restore the monastery in Sázava. For this purpose, the Benedictine monk and priest Method Klement moved from Emmaus to Sázava in 1940, to become a parson at the St. Procopius’s temple. However, the restoration of the monastic life based on the Slavic legacy of St. Procopius failed due to WW2 and the following communist totalitarian regime. Father Klement at least successfully restored the reverence of St. Procopius, revived the spiritual life at the parish, and had the temple repaired, including its equipment. The repairs included the decaying pillars of the unfinished Gothic temple, and the experts started taking interest in the history and archaeology of the monastery. Father Klement also discovered the “Cave of St. Procopius”, which gave birth to the idea to connect the cave with the temple crypt and enable access to the public, like in the Middle Ages.

Nationalization and the era of socialism

The area was nationalized in 1951, and managed by the National Cultural Committee. A restoration concept was made, primarily involving unsuitable modern modifications made by secular owners; the newly discovered Gothic paintings in the capitular hall were revealed and restored. Even Father Klement took a major part in the restoration, before leaving Sázava in 1957. In the second half of the 1950s, the local glassworks Kavalier started using a part of the area, setting up the exhibition of technical glass on the first floor of the main monastery building. In 1962, the area became the National Cultural Heritage Site, and was thereafter managed by the National Heritage Institute. In the late 1960s, archaeologists and art historians started taking interest in the monastery once more. The Archaeological Institute of the Academy of Sciences organized a systematic archaeological research that lasted until the 1990s. The research managers were Květa Reichertová and then Professor Petr Sommer. Several new studies and concepts were made for the exhibition that would commemorate the Slavic history of the monastery. Once the interiors were repaired, the exhibition “Old Slavic Sázava” opened in the ground floor in 1983, prepared together by the archaeologist Květy Reichertové, expert in Slavic studies Marie Bláhová, and historian Václav Huňáček. The exhibition not only presented the Sázava monastery but also the Slavic mission of St. Cyril and St. Methodius in the Great Moravia, the education in the first stages of the Bohemian Přemyslid state, and also the Slavic Emmaus monastery founded by Charles IV in the New Town of Prague. The archaeological, historic and linguistic research was used.

After the Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution in 1989 gave new hope to the Emmaus Benedictines, the parish, and the heir of the last secular owners that the property, nationalized in 1951, can be returned. And indeed, Ms. Marie Hayessová of the Schwarz family obtained the family inheritance in 2003. In 2006, she sold the property back to the state. Recently, pursuant to the act on the church restitution from 2013, several parts of the area were returned to the Roman Catholic Parish Sázava – Černé Budy, and others to the Abbey of Holy Mary and St. John the Baptist, in Prague-Emmaus.

The current manager of the area, the National Heritage Institute, first focused on the repairs of the roofs and facades of the church and the convent, on the continuous maintenance of shingled roofs of the former abbey and parish house, on the reconstruction of utility networks, and, primarily, on the ongoing reconstruction of the decaying pillars of the unfinished Gothic three-nave structure. The Institute also had the northern garden restored, and provided there access for the public. However, no large investments or concepts were possible during the years of restitution uncertainties. This changed to some extent when part of the area was bought from the secular owner in 2006. Since 2007, large and detailed research was continuously done, with studies and projects involving more or less the entire monastery area. Sewers and power lines in the church and former abbey were reconstructed and upgraded; the roof frames and roofing were repaired on the convent building and the Chapel of Holy Mary. Once the frescos in the cloister were discovered in 2007, their gradual restoration began.